Gender fluidity and climate change are not the hot-button topics you’d expect from an author writing more than 400 years ago.

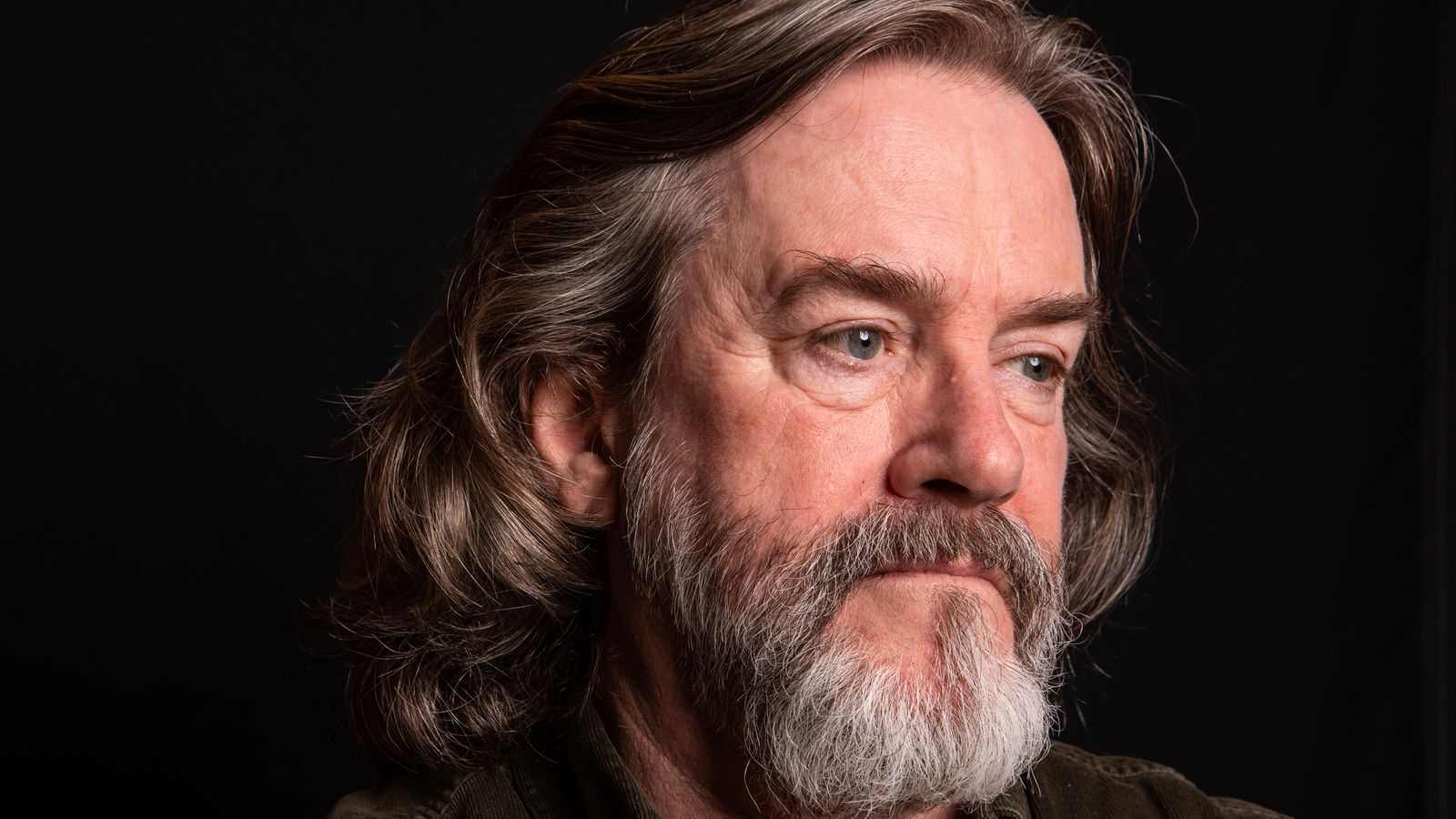

But it’s Shakespeare‘s “contemporary” outlook that means he will “last a great deal longer than the culture wars,” according to Royal Shakespeare Company (RSC) artistic director emeritus Gregory Doran.

While parts of the Bard’s texts recently got banned in some US schools due to their sexual content, Doran tells Sky News: “He’s robust, he will always be there. Those plays will always be there.

“If that one single book has lasted 400 years, he is going to survive a few people taking offence.”

And as for trigger warnings – a modern addition to any potentially distressing content an audience might encounter – he finds “the hypersensitivity absurd”.

Doran, who alongside Dame Judi Dench has written the introduction to a new edition of Shakespeare’s complete plays marking the quarter centenary of their original publication, says it’s an “honour” to be involved with the First Folio, which is now considered one of the most influential books in history.

Without it some of Shakespeare’s most famous plays – including Macbeth and Twelfth Night, along with its much-quoted All The World’s A Stage speech – would have been lost to history.

While 750 copies were published originally, there are now only 235 copies known to remain – with just 50 of those in the UK.

In 2020, a copy was sold for over £8m, making it the most expensive work of literature ever to appear at auction.

Shakespeare is a ‘magnet’ for current obsessions

Doran – who has directed or produced every one of the First Folio plays – says while he didn’t set out to work through them all, he did decide not to repeat plays (although he relaxed his self-imposed rule for a Japanese language version of Merchant Of Venice performed in Tokyo, and A Midsummer Night’s Dream, which he first worked on early in his career, and later revisited).

While he has directed and produced work outside of Shakespeare – including contemporary plays and musicals – he admits “Shakespeare has been the spine of my career.”

It seems once the Bard bug has bitten, it’s hard to tear yourself away.

Because once you work with Shakespeare’s texts as a director, Doran thinks other playwrights struggle to live up to his example.

He adds: “Every play takes you to a different world.

“Shakespeare is like a magnet that attracts all the iron filings of what’s going on in the world… contemporary issues or themes or obsessions.”

He recalls a line in Cymbeline, where the heroine of the play, Imogen – while dressed as a boy – meets a group of young men and says to the audience: “I’d change my sex to be companion with them.”

Doran explains: “The concept of your sex not being a single constant thing, but something that you – even if you can’t – would have the desire to change, that Shakespeare expresses it 400 years ago, it’s just not what I was expected to read.

“In a world of constant conversations about gender fluidity and non-binary, suddenly Shakespeare is articulating this young woman’s desire to try out another gender. And I just find that astonishing.”

Doran also flags Titania in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, who gives a speech on climate change.

He says: “Everyone thinks A Midsummer Night’s Dream [happens] on a lovely summer’s evening, but it’s all taking place in the rain. And [Titania] says this is our fault that the weather is changing. She says: ‘The seasons alter.’

“It’s just so surprising to hear something so contemporary.”

Trigger warnings about balloons ‘absurd’

Far from a text purist (his 1999 RSC production of Macbeth worked in jokes about Tony Blair) Doran does believe updates should be handled with care – and he certainly isn’t a fan of recent bans on Shakespeare at schools in Flordia.

He says: “You can cut [Shakespeare] in performance. So, if there’s a bit you don’t want to deal with, then don’t deal with it, it’s fine.

“But I would say that certainly students should be given access to the whole thing and the context in which it was written, which is 400 years ago. And attitudes have changed.”

While society has evolved since Shakespeare’s days, Doran’s not a fan of the relatively modern phenomenon of trigger warnings, saying: “I sometimes find the hypersensitivity [around them] absurd.”

Referring to his 2022 production of Richard III, which had a balloon popping in the first soliloquy, he says: “We all have a reaction when someone has a balloon, you kind of cringe waiting for it to pop, but that doesn’t need a trigger warning.

“And in fact, if you’re given a trigger warning, then the danger is that people are not listening to what the rest of the play is because they’re anticipating something they’ve been told is going to happen.

“It’s an absurd thing to say, ‘There are latex balloons in this production,’ when you could also say, and children are murdered, or people are abused and killed [in this play].

“But that’s also a spoiler, you don’t want to hear about that to begin with.”

From actions on stage to behaviour off of it, Doran is aghast at the idea of an audience code of conduct, saying such a list of stipulations would signal “too much of a nanny state”.

He goes on: “I know actors who if the audience are coughing they get furious, and other actors who say, they’re coughing because they’re bored.

“So coughing is very difficult, but I’m not sure that putting in the programme ‘don’t cough’ actually helps them not cough, you know?”

Doran says actors and fellow audience members should be able to keep any poor behaviour in check.

“Any audience is a live thing, and as an actor, you have to be in control of that,” he says.

“Like any good stand-up comedian knows how to, if there’s a rowdy section, then you’ve got some put-downs of those heckles and you get them onside.

“There are other ways of heckling, one of which is to direct the line directly at the noisy person or the person who’s on their phone… They can suddenly realise, because there are sometimes young people who think they’re in front of a television screen.”

Shakespeare would have ‘shrugged off’ his national poet title

A director known for his progressive attitude towards diverse casting during his decade in the RSC’s top job, he acknowledges not all sections of the viewing public were fans of his approach.

His RSC firsts include an all-female director season, a gender-balanced cast for a production of Troilus And Cressida and hiring the company’s first disabled actor in the role of Richard II.

Doran says he was not surprised by the backlash some of his choices attracted, saying: “The point is not to provoke, but provocation isn’t a bad thing.

“We fetishise Shakespeare.

“We can regard Shakespeare as being the upholder of a particular kind of national sense of identity or spirit.

“I think Shakespeare would have shrugged off any such kind of attribution.”

Some might question whether it’s problematic to centre a white, male perspective and say it speaks for everyone.

But the problems occur, Doran says, when we try to fit Shakespeare and his work into boxes that don’t necessarily fit.

Click to subscribe to Backstage wherever you get your podcasts

He says: “In the 18th Century, there was a huge effort to make Shakespeare – and it continues to this day – the great national poet, the speaker of empire, as it were.

“And if you’re doing that, then you have to erase the bits where maybe there is homosexual desire. We can’t have that, so we’ll write it out.”

He flags that of Shakespeare’s 154 sonnets, 126 of them are from a man, addressed to another man.

Doran goes on: “In the 19th Century… there was an absolutely identifiable process of the heterosexualisation of the sonnets.

“So, the pronouns were changed, because we couldn’t, if we were having Shakespeare as our national poet, we couldn’t have him being gay.

“We all make Shakespeare in our own image… Or if you don’t like Shakespeare, you point to the bits that are difficult and may be misogynist or racist or appear to be so, and we hold those up as reasons why we should no longer study it.

“He’ll last a great deal longer than the culture wars.”

William Shakespeare’s The Complete Plays will be published by The Folio Society on Tuesday, and My Shakespeare: A Director’s Journey Through the First Folio by Greg Doran is out now.