With the latest iPhone now in people’s hands and Google’s annual Android flagship not far behind, it’s a pertinent time to release a film about the once iconic device that paved the way for both.

BlackBerry hasn’t appeared alongside them on shop shelves for years, and any remaining devices were effectively killed off last January when the company behind them ceased support.

It was an undignified end for a gadget that changed the world, one that became not just ubiquitous with boardrooms and offices (including a certain oval-shaped one), but a true fashion statement.

Thrusting it back into the spotlight in 2023 is director Matt Johnson, who hails not far from BlackBerry’s Ontario HQ.

And yet, against all odds, he says he has no history with the world’s first smartphone whatsoever.

“The timeline of the product was one of the main things I was interested in,” the 37-year-old says.

“A film about the late 90s/early 2000s shift from a more analogue world to a more digital world.

“That’s when I was quite young and a great opportunity to explore that cultural space, all where I grew up.”

‘Hacker-style’ nerds who changed the world

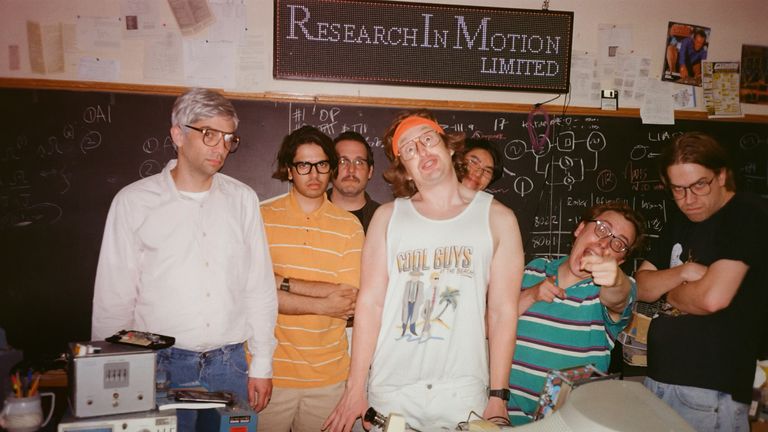

BlackBerry (the film, not the product) picks up in 1996 at tech firm Research In Motion.

At the time, its ragtag crew of engineers are unaware they’re working on perhaps their country’s most famous export since maple syrup.

Mike Lazaridis (Jay Baruchel) and friend Douglas Fregin (Johnson) suspect their “PocketLink” idea for a phone that does email is good, but lack the business sense to turn concept into reality.

Johnson says they were interested in solving practical problems, but had “no vision of a cultural revolution”.

Enter the ruthless and opportunistic Jim Balsillie (Glenn Howerton), who sees enough potential in the pitch to brute force his way into becoming co-CEO and set up a pitch with the US telecoms giant that would become Verizon.

The film, based on the book Losing The Signal, takes some liberties with the BlackBerry story – and the real players involved have said some portrayals are closer to satire.

Balsillie’s depicted as a hilariously foul-mouthed demon of the boardroom, while Lazaridis and Fregin lead a team of “almost hacker-style” nerds who love video games and office film nights.

What the film undoubtedly nails is the BlackBerry brand’s ascendancy to stardom.

Cracking the market

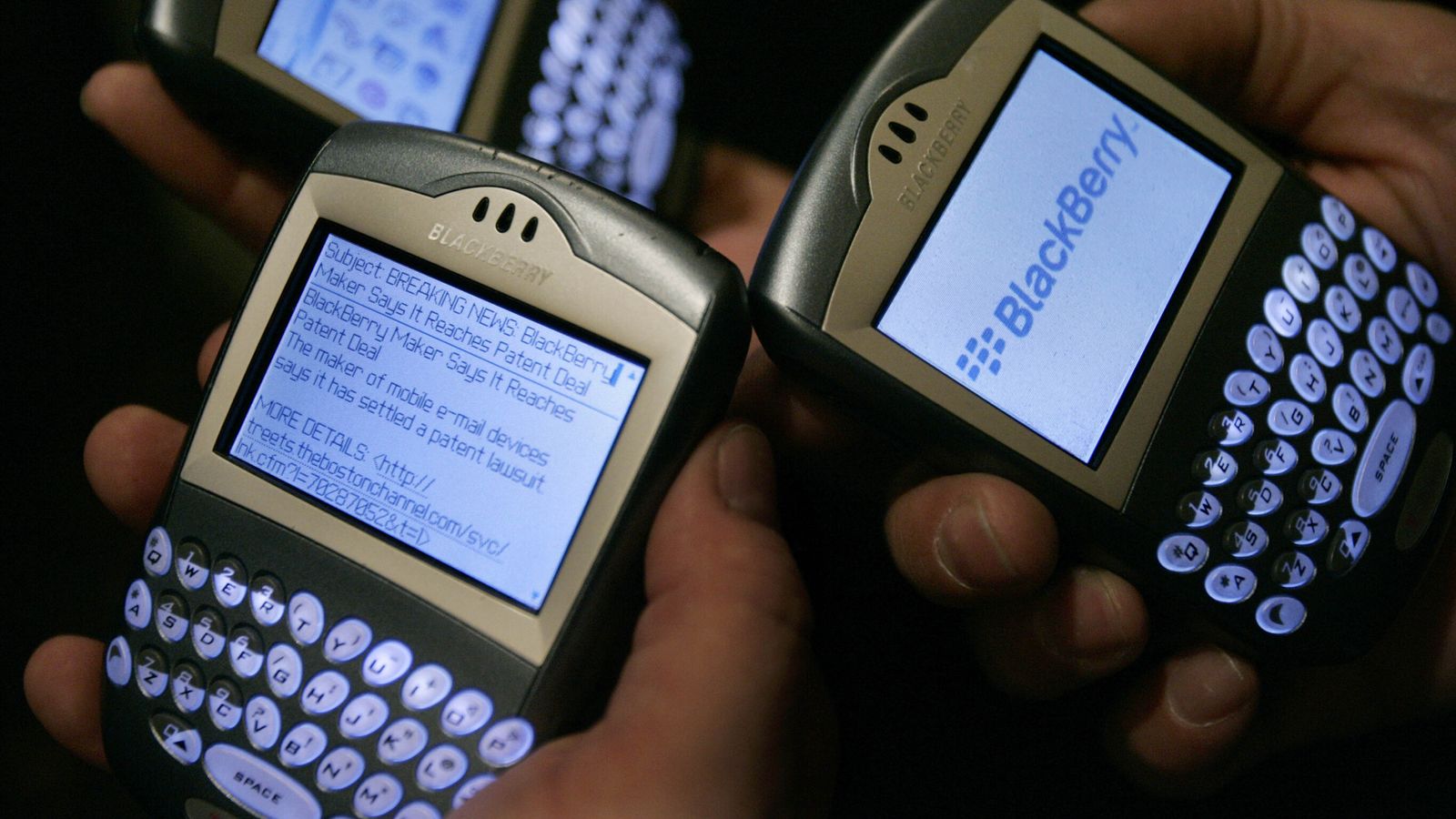

The first device in 1999 had email and two-way paging, with a keyboard and modest monochrome display.

By 2002, calls, texts, and internet browsing were features of an increasingly popular product with business types.

But the game-changing launch of BlackBerry Messenger in 2005 took it truly mainstream, bringing WhatsApp-style encrypted messaging we now all take for granted.

The world’s addiction to typing on the go saw “CrackBerry” named Webster’s Dictionary’s word of 2006.

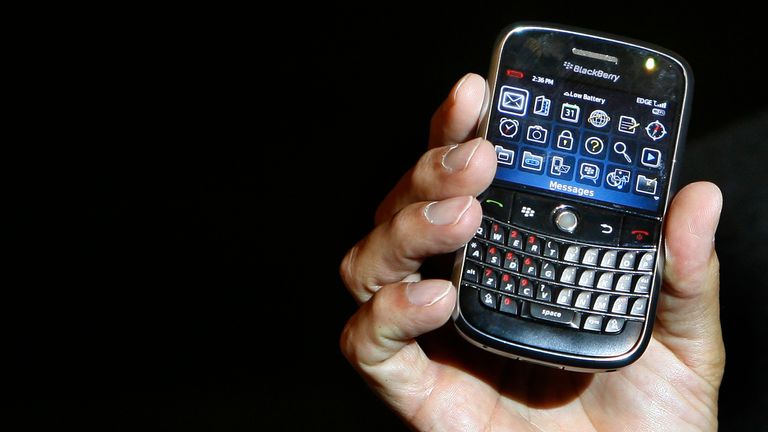

It was the phone of choice for millions of people, endorsed by celebrities and even the US president.

At its peak, BlackBerry controlled almost half of the global smartphone market.

Apple makes its move

But 2007 heralded the iPhone – and the world would be about to change all over again.

Steve Jobs ruthlessly mocked the BlackBerry’s reliance on a keyboard during the grand unveiling, as observers swooned over the large multitouch display in his hand.

For many analysts, it marked the beginning of the end for BlackBerry.

For Johnson, it wasn’t necessarily the iPhone itself that killed the BlackBerry – but its creators’ response to it.

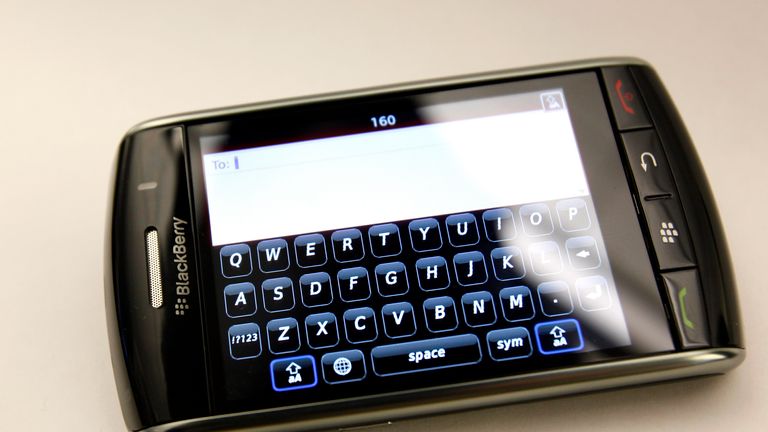

It saw the company hastily assemble a Frankenstein-like competitor which tried to combine a touchscreen with the satisfying clicks of a physical keyboard.

“It’s a keyboard… on a screen… on a keyboard,” is how Baruchel’s Lazaridis pitches it to his engineers, tragically unconvincingly.

The resulting BlackBerry Storm, released in 2008, was a disaster.

Issues with the new touchscreen, which had one enormous button underneath, saw Verizon have to replace all one million devices it sold and claim $500m in losses.

‘How do you do, fellow kids?’

It put the Canadian company on the back foot, and left its executives grappling with an identity crisis as Apple’s trendsetter went from strength to strength.

BlackBerry still had its loyal users, with one Barack Obama among those happily using them for years after.

The company even welcomed Queen Elizabeth II for a visit to its headquarters in 2010.

But by then it was clear the company’s direction had become muddled, and the masses and phone carriers were batting their eyelids in the iPhone’s direction.

BlackBerry had gone from status symbol to “how do you do, fellow kids?” in the blink of an eye

Blind revolutionaries

Johnson sees BlackBerry’s downfall as a cautionary tale, but also something of a tragic one.

“They set up the scaffolding for a revolution, but then didn’t realise one was about to happen,” he says.

“It wasn’t that the iPhone was just a better product,” says Johnson.

“It had more to do with the vision of a company like Apple compared to Reality In Motion.

“People say they’re part of the ‘Apple ecosystem’ – the brand means more than the products.

“BlackBerry just did not do that and weren’t interested in that.

“And by the end, those original engineers end up so disillusioned and alienated from the thing they built, I don’t think they even believe they built it.”

BlackBerry kept chipping away at iPhone-style touchscreen devices, but found itself swimming against a tide made even stronger by the popularity of Android.

In 2016, the firm gave up making phones and transitioned to being a software security business, licensing out the BlackBerry name for other manufacturers to give it a shot.

The last hurrah was 2018’s BlackBerry KEY2 LE from China’s TCL, an awkwardly assembled jack of all trades that unceremoniously stuck a keyboard at the foot of a touchscreen.

It could hardly have been further away from Lazaridis’s original “texts, calls, email” vision for a phone, one which Johnson thinks might yet make a significant return.

Nostalgia-driven “dumb phones” from Nokia have seen a resurgence as users seek a detox from social media, while newcomers like the Light Phone proudly boast of offering nothing but texts and calls.

“I think if BlackBerry had reverted to that philosophy, they might’ve found success,” he says.

What’s certain is that no company can afford to rest on its laurels in the constant churn of Silicon Valley.

The modern smartphone may be lacking for innovation, but as BlackBerry and iPhone both proved, the future can emerge in no time at all.

BlackBerry releases in UK and Irish cinemas on 6 October.